A Writer Takes His Pen to Write the Words Again Lyrics

Writing Lyrics With Bob Dylan Is Weird

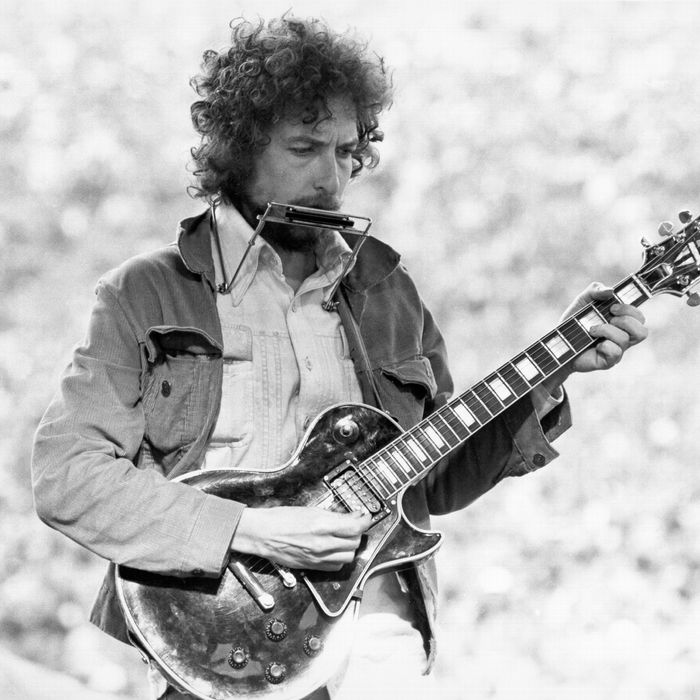

SAN FRANCISCO, CA - MARCH 23, 1975: Vocaliser/Songwriter Bob Dylan performs at Kezar Stadium in San Francisco, California, March 23, 1975. (Photo past Alvan Meyerowitz/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images) Photograph: Alvan Meyerowitz/Getty Images

Carole Bayer Sager was one of the almost prolific songwriters of the 1970s, working with artists similar Neil Simon, Carole Rex, Michael Jackson, Aretha Franklin, and today'southward winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, Bob Dylan. The following is an extract from Bayer Sager's new memoirThey're Playing Our Vocalin which she describes a 1986 writing session with Dylan.

*******

I'k sure the idea of me writing with Bob Dylan sounds as alien to you every bit it was to me when he chosen. The whole idea of collaborating with him seemed ridiculous. If anyone felt like a self-contained solo artist to me, it was Dylan.

He changed a generation. No, he wasn't having hits when we wrote together, but he was nonetheless tirelessly releasing new records full of ambitious material and was e'er taken seriously because he was Bob Dylan.

I had met Bob a number of times. His girlfriend at the time was my friend Carole Childs (formerly my old friend Carole Pincus), and she suggested nosotros write together. Bob liked the thought, so one twenty-four hour period in the spring of 1986 nosotros institute a solar day for me to drive out to his Malibu ranch and run into what we might come with.

I drove out to where Bob had lived for years now. It was farther than nearly homes I knew out there, only what surprised me (and yet did not surprise me the minute I put a Bob Dylan filter over it all) was the kind of rundown feeling the place had. The greenery was growing any way it wanted, and there were no gardeners shaping the plantings. It looked a lot like Bob looked to me — unkempt, frayed, and worn. His beard was growing in all directions, too.

He actually was a man of few words. "Let's become out to the befouled," he said. How I wished I had the cocky-credence to be in cowboy boots, but they didn't have high plenty heels. The ground on the walk from his primary business firm to his barn was more than uneven than his beard or his shrubbery. A divot here, a clump of soil in that location; I prayed that breaking an ankle would not exist part of my "writing with Bob Dylan" story. His big, musty barn reminded me of a summer military camp in the middle of wintertime.

Ii single beds faced each other, with random quilts and guitars lying around. He sat on 1 of the beds and I just sat myself down on the other, facing him. Nosotros were around 5 feet away from each other, which is unusual since I usually sit very shut to where the composer is seated. He picked upwards one of the two guitars that were sitting against a cracked wall. An old forest upright piano was in a far-off corner waiting to exist played. I had a feeling it had been waiting quite a long fourth dimension.

I had to focus on why I was sitting facing Bob Dylan because there was a part of me diddled away by what an unlikely pair we fabricated together — he completely disheveled from caput to toe and I in total makeup, tight jeans, tee shirt and studded leather jacket. I was wearing my "faux" rock 'n' roll wait and failing miserably, and he could accept told me he had come in from only rolling around with some farm animals and I would not have disbelieved him. He looked like he hadn't bathed in weeks.

In all truth, though he was an icon, I was a not a follower. I missed the Dylan Revolution somehow, with the exception of a few classics like "Blowin' in the Current of air," "Like a Rolling Stone," and "Lay Lady Lay." So I knew the hits, but I was listening more than to the polished sound of popular and R&B. I appreciated Bob's thorny poetry as a lyricist, simply I was always in search of a great tune. Friends whose sense of taste in music I respect have played me some of their favorites and when I listened, though I appreciated how very good some of the lyrics were, they didn't hit me in my solar plexus because at that place was no melody to speak of.

Still, I sat in his befouled and I was completely enlightened that This Is Fucking Bob Dylan!

I had my usual xanthous lined legal pad and he gave me a pen when I couldn't discover mine in my overstuffed bag which included a wallet, a menu example, a makeup bag in case I was sleeping over, Kleenex, Chapstick, a small collection of star crystals in a pocket-sized silk pouch which I carried because I was afraid to stop conveying them in example they were protecting me, a croc case for my Lactaid and my Stevia, cards with people's names on them I no longer knew, a mirror given me by Elizabeth with undistorted magnification, my eyeglasses, a condom tip that a dental hygienist had dropped in i day, and scores of useless other things that merely kind of piled up in at that place .

"Thank you," I said, taking my head out of my handbag long enough to accept his ballpoint pen, which I wished had a thicker tip.

I refocused. "So, practise you accept any ideas of what yous experience like writing?"

"Well, I've got a little bit of an idea."

He mumbled his words very softly. I idea he said "I godda libble bid a deer."

He started strumming his guitar. I had to admit, this was cool. Bob Dylan strumming a guitar. And then he began humming a melody. It was a simple one. He didn't ask me if I liked it only he sang,

"Something about you that I can't shake."

And he played the melody to the next line and I nervously said, "Feels like information technology'south more than my middle tin can take?" I was kind of writing and asking a question at the same time. And he sang,

"Don't know how much more of this I tin take / Baby, I'grand under your spell."

Usually the composer waited for me to come up upward with the lyrics, playing the tune for me until I heard words I wanted to write. In this case, Bob was way ahead of me. "That'south good," I said, feeling more similar a stenographer than a lyricist.

As we continued I kept offering him lines. Sometimes he'd say, "I like that" and I would be so happy equally I wrote something down.

In the eye of the song, I went over to await at his lyric sail and I felt similar an eighth grader who was trying to cheat on her English test. Bob was substantially the pupil you didn't effort and cheat off of. He was hunched over his paper, hiding it with his left hand and his curly head of hair.

"Can I see?" I asked.

Near of the lyrics of mine that I idea he'd liked weren't even written down — but i or 2 lines.

Finally, I said, "I feel similar y'all don't really need me here writing this with you because y'all seem to have your own thought of what the lyric should be." I was being honest.

"No, I need you here," he said. "I wouldn't be writing this if you weren't here."

He played the same melody once again. Another verse.

I was knocked out loaded in the naked night

When my dream exploded…

And I said, "What almost 'and I lost your light'?"

He sang, I noticed your light.

Well, that was a little something. He continued, "Baby …"

I said, "How about, 'Baby y'all know me so well.'"

He was serenity and so sang, "Infant Oh what a story I could tell."

I would toss out a line and he would say, "That's good," and sometimes even sing the whole line, so by the time we finished I thought I had contributed maybe twelve lines to the lengthy song.

A few days afterwards he had laid a rough version down on a cassette and sent it to me.

Of the twelve lines I idea I had written, possibly there were 3 or four left in the vocal. I immediately called him.

"Bob…"

"Hey."

"Listen, I don't think it'due south fair to you to say we wrote this song together. So much of the lyric is yours. I just don't feel right taking a credit."

"Never would take written it if you weren't here," he said again. "And you wrote some practiced lines."

Most of them never to be heard, I thought.

"Well, I don't feel right taking fifty per centum of the song," I said, and he quickly said, "Well, how 'bout you own half of the lyric and I'll ain one-half."

"Sure, that sounds better."

When the record came out he called the whole anthology Knocked Out Loaded, a line from "our" vocal. I would have been proud, but that wasn't one of my 5 lines. Anyhow, it gave me corking bragging rights, because how many people can say they wrote a vocal with Bob Dylan? He worked with very few writers during his career and I certainly know why. Withal, it was bizarrely thrilling,

USA Today said in the last paragraph of its review of Knocked Out Loaded, "It's ironic and advisable then, that the anthology's best song, 'Under Your Spell,' was written with onetime-fashioned tunesmith Carole Bayer Sager. Dylan tin't help only sing its frail melody, and when he reaches the concluding line, 'Pray that I don't die of thirst two feet from the well,' quondam friends volition exist happy to give him water."

I loved that terminal line as well. I wished it was mine.

From They're Playing Our Song: A Memoir past Carole Bayer Sager. Copyright © 2022 past Carole Bayer Sager. Reprinted past permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved.

mendezdebectiand75.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.vulture.com/2016/10/bob-dylan-carole-bayer-sager-book-excerpt.html

0 Response to "A Writer Takes His Pen to Write the Words Again Lyrics"

Post a Comment